I wrote this article for the very local, small-distribution newspaper in Takilma, the community where I’m currently based in southwestern Oregon (Takelma land).

What’s the plan, Takilma?: Communal land succession & the opportunity of this moment

By Eliot Feenstra

This is intended as the first article in a series exploring the topic of communal land succession.

“It’s what presented itself,” Beth began, when I asked why she and Mark chose to live communally. “We didn’t arrive with ‘this is what we’re going to do’—we had our dreams, thoughts, were certainly troubled by the outside world.”

Mark agreed, “Coming of age during Vietnam, wanting to try a different way than American-pioneer-spirit, do-it-all-yourself, get-your-own-little-piece-of-land-and-raise-yourself-up-by-your-own-bootstraps and all that…I always had a dream of raising food, growing food and I knew I couldn’t do it on my own.”

“We couldn't have done what we did individually. It had to be cooperative to be successful,” he added.

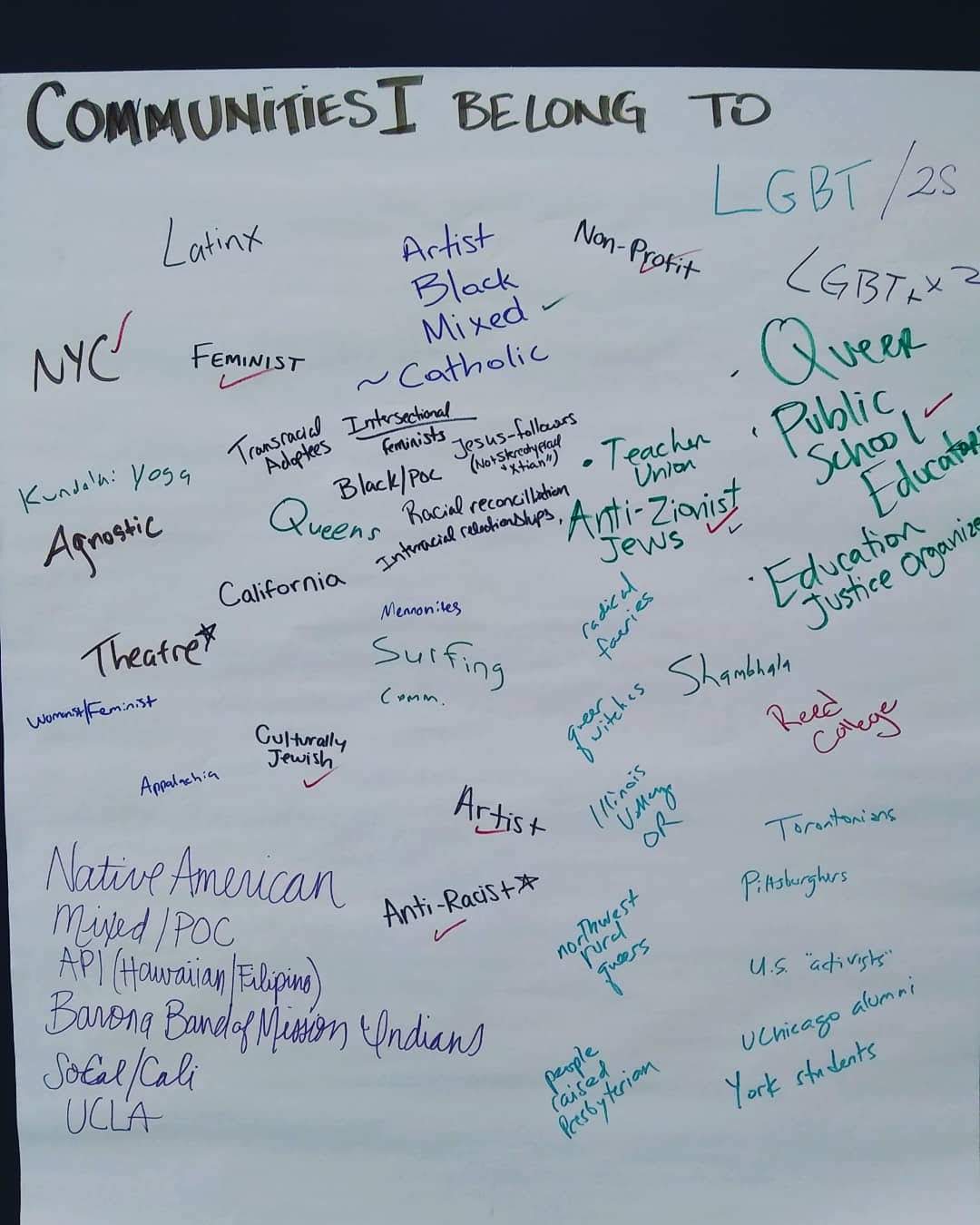

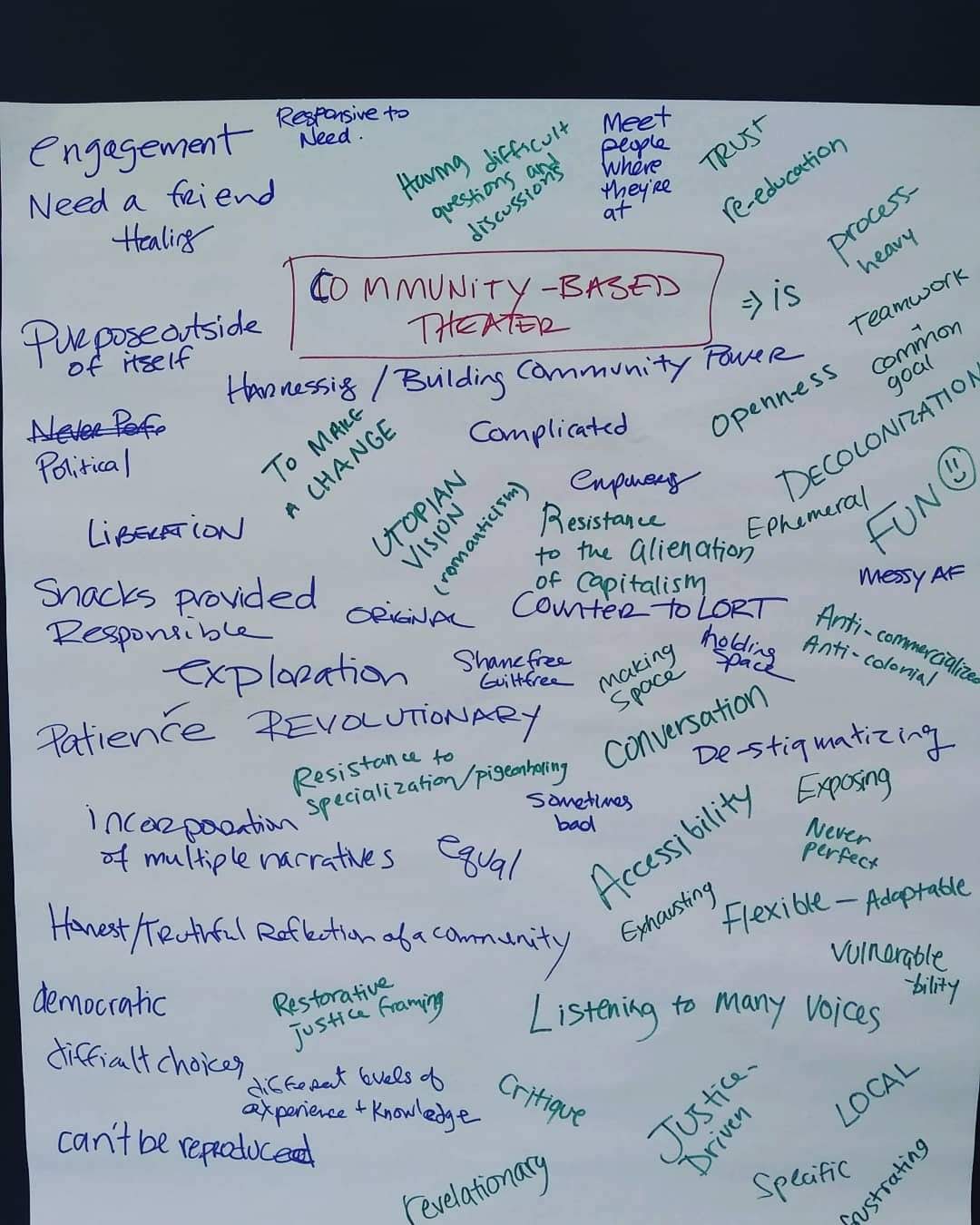

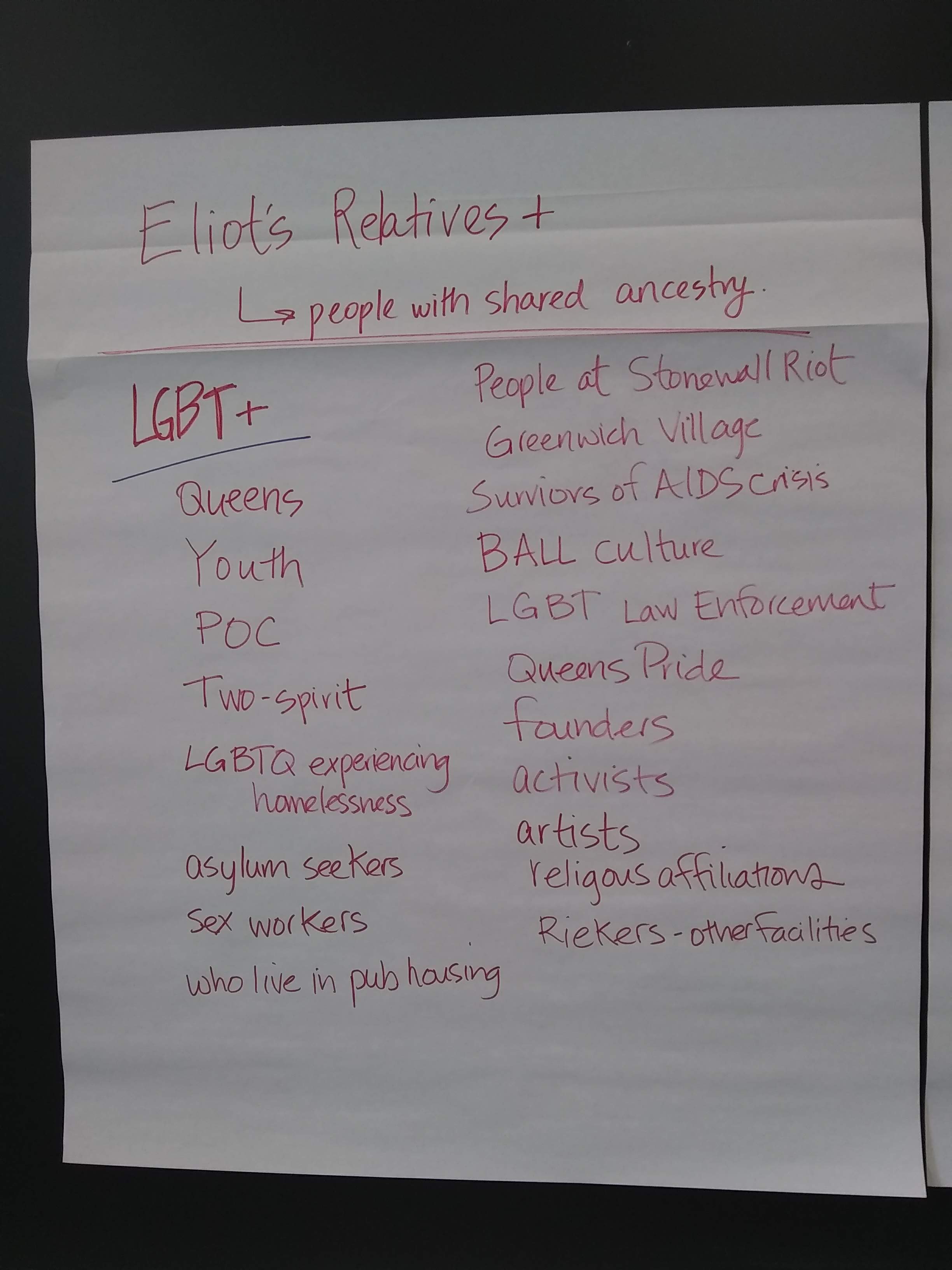

Part of what I love about living in Takilma is that I feel part of a movement that is now 50+ years old. As an artist, theatre-maker, activist, organizer, I see myself building on the incredible legacy and wisdom of folks from the 70s—from the Diggers to intentional communities. I’m so grateful for the urban spaces that radicalized me and I want those spaces and experiences to stay alive, to keep being there—living examples of sharing, resisting and living well, fighting the system and feeding and loving each other.

We are in an phenomenally abundant and unique region with an amazing depth of history, lived experience, and accumulated knowledge about communal living and land stewardship held by aging folks. As a younger person in this community, that’s led me to wonder what the plan is for Takilma’s future…and particularly for the future of the communal land projects which are, to me, emblematic of the dreams that brought many folks here. What’s the relationship between our elders in the movement and us younger folks and emerging leaders and activists who share similar ideals to the hippie generation? Will Takilma become a ghost town of summer homes for children of hippies?

--------------------------

Mark said, smiling, that his hope for the Meadows in 50 years is that “the land is groaning with pleasure under the weight of all the old growth.”

When I asked Mark and Beth about the future of the Meadows, they said their vision is that the conservation easements will protect the land from development. “It would be ideal if others could enjoy the physical life of being here. … But bottom line, the land is essentially going to be okay. It doesn't require humans to be okay,” Beth said.

“The Meadows” is protected by a conservation easement held by the Southern Oregon Land Conservancy, who are obliged to protect the land from development in perpetuity, regardless of who holds the deed. A conservation easement like this costs between $20-30,000 to set up, Mark said, but it often can still save the landowners money by decreasing income taxes. The easement decreases the assessed value of the land, since timber value is no longer part of the calculation of the land’s value.

Beth called that the process of setting up the communal legal structure—which went through many iterations before becoming the mutual benefit corporation that it is today—“super tedious” and said it is one of the “culling things” a group might go through. “It really does get into some incredible minutiae of what your values are. [It’s been a] many, many year process of sorting it out so that we all feel acknowledged with some basic evolution with our values…Values don't necessarily stay the same over this many decades.”

--------------------------------

Tediousness might be one challenge for succession planning; but another is that communal land ownership pushes against the core American ideal of individualism and private property ownership, and discussions about inheritance often bring up those ideas.

Mark identified one of the core challenges for communal land: “How does it get carried over? You can't have it be a really good investment for yourself and still keep the land together. You have to decide what level of compromise you want.” Holding the land above individual interests is part of what has kept Christy, Romaine, Mark, Beth, Linda, and Sitting Dog, who recently passed away, together at the Meadows for so many years. “We're nature worshippers. We think ownership of land is a myth--it's a game, it's not real but we chose to play it so we wouldn't be homeless and so we could steward this place. And we all recognize that...we don't own this place, it owns us. We're loyal to taking a little piece of the earth and trying to nurture it and having it nurture us.”

Between 1965 and 1980, Takilma was, as we all know, a hub of communes like this, a few of which are still communes today. But for some young folks now who have affinity with these communalist sentiments or moved to this area with a similar dream, the Valley may not seem as welcoming as it did in the 1970s. One young person I spoke with expressed that our generation (“millennials”) are perceived as ‘moving around a lot’ but it’s often just because we are dealing with persistent housing insecurity. “Why can a guy with dreads who’s so high he can’t keep his spit in his own mouth find housing in Takilma and I can’t?,” this person asked. Perhaps the equivalent imperative to ‘drop out’ for young people in the 60s and 70s is, these days, an imperative to get more engaged—we’re living in a time of unprecedented ecological crisis that’s calling a lot of us to action and demanding that we cannot afford to disengage. When I lived in Takilma in 2015, we had a monthly cards game for folks who were 20s-30ish without kids; all of those folks have since moved because of lack of job prospects, adequate housing, or sense of opportunity.

While there is a lot of housing in the Valley, much of it is not publicly available…for a lot of reasons. The positive side of this is that Takilma is a very relational and relationship-based community: there is an incredibly dense network of relationships, mutual support, barter, and ways that people show up for each other. As a newcomer, I have been awed to see the smoothness with which meal trains have been coordinated and resources gathered. Doors open. The draw-back (as I see it) is that for a newcomer to this community who might share values and ideals but not immediately fit in, wherever a door could open, it could also close. As Abigail at Rogue Farm Corps said about farming, “All the interactions that happen that lead someone from being curious about farming to becoming a farmer to start a business to being successful---all along that path you can have doors open for you or you can have doors close and that has a lot to do with your identity and privilege…racism, basically.”

There are hundreds of acres of land which was and perhaps may still be held in various versions of communal ownership, likely mostly developed by folks riding the radical wave of the 1960s-70s. While setting up those structures was tedious, as Beth described, can these land projects and legacies of Takilma’s past and present support a future generation of radical environmental and peace activists? Are millennials willing to commit to the tedium of agreements, contracts, and labor required to transfer so many years of expertise, sweat, and experimentation?

A CRITICAL OPPORTUNITY

I think that this topic of communal land succession is an important issue for a number of reasons.

This moment is an opportunity to be intentional about the future of our community.

Land stewardship is a multigenerational project. Building soil, tending waterways, learning how to live in good relationship with the earth--that’s many generations of knowledge and practices.

There is a lot of knowledge and wisdom in our community about communal living, growing food communally, and communal land management which are a huge resource for the ‘next generation’ of farmers, activists, and land stewards. So much labor and love has been put into building this community that I hope the ‘next generation’ can learn from, respect, and carry these stories and ways of knowing.

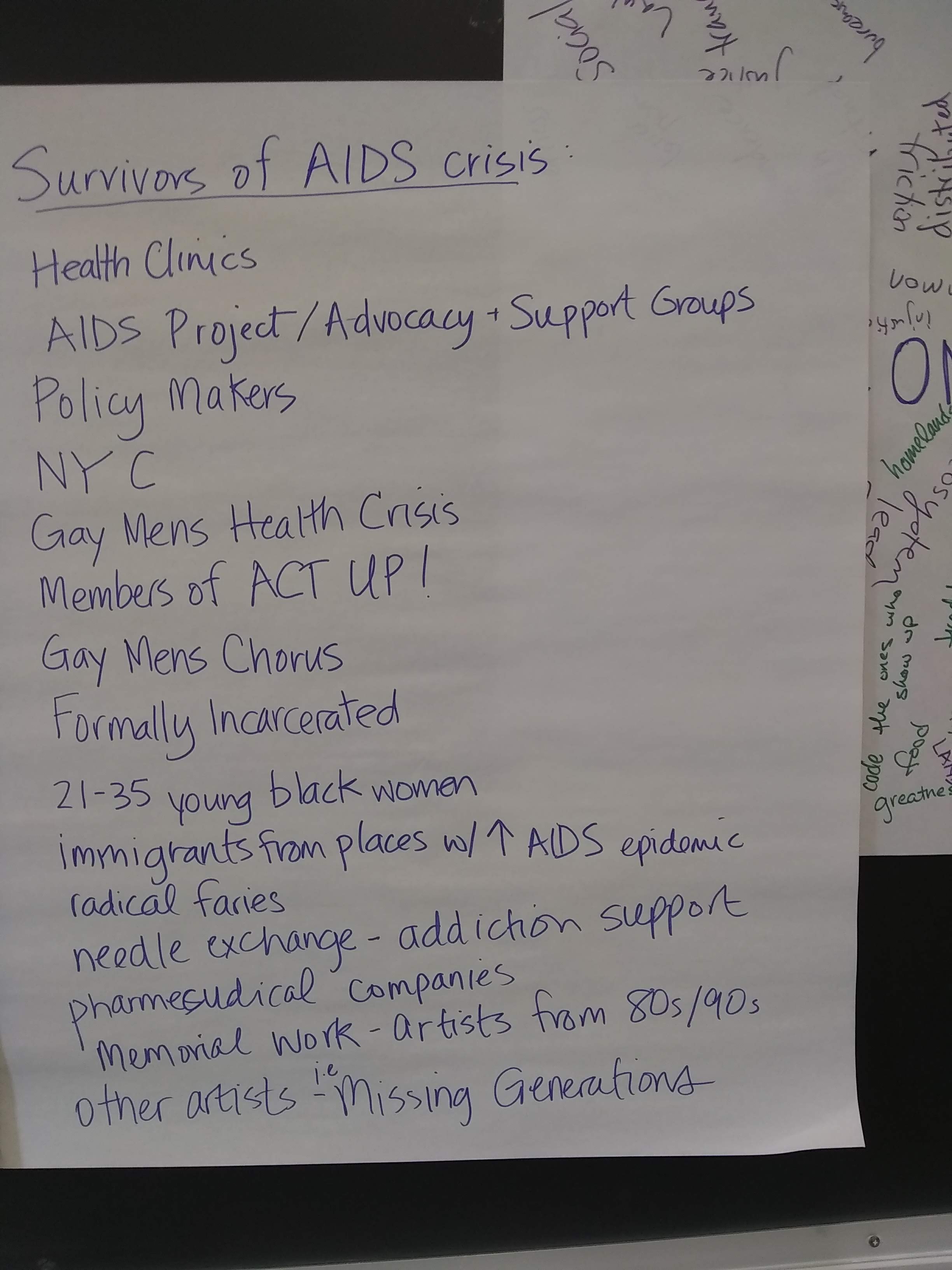

Access to land is an issue of justice and power. Land access has been systematically removed from Black and indigenous communities; this land, when it was first claimed by settlers and miners, was stolen from the Takelma people. A 2016 study by the USDA called “Who Owns the Land” revealed that white Americans own more than 98% of US land; by contrast, black people compose 13% of the US population and own less than 1% of rural land. The racial disparity in rural land ownership has deep historical roots.

Over the next two decades, Baby Boomers are expected to transfer $30 trillion in wealth to younger generations: the greatest “changing of hands” that has happened in American history. Journalists are calling this “the great wealth transfer” and it represents an opportunity to redistribute wealth, including land, more equitably.

There are people who already live in or want to live in this community who can’t afford to be here or find places to live; in part this is a result of the inflated prices because of the cannabis industry. According to a recent UCAN study, the average cost of an apartment for a single person in Josephine County is $850/month; most adults are ‘severely rent burdened,’ meaning they pay over 50% of income for housing.

Overall, Josephine County, as with many rural communities, has an aging population and will need support and younger folks to be involved in their care and in stewarding our community through the next 30 years; just as younger land stewards and activists can benefit from the mentorship, experience, and resources of older folks.

The opportunity is self-evident but the questions remain: where is land succession working, or not, in our community, and what supports exist for navigating this process?

“CHANGING HANDS” - RESOURCES FOR LAND SUCCESSION

One resource for folks looking for support in connecting with a younger generation is Rogue Farm Corps’ “Changing Hands” program. “Intergenerational succession is a huge need across farm projects and businesses,” said Abigail Singer, executive director of Rogue Farm Corps. While their work is mostly geared toward farmers, the Changing Hands program offers workshops, training, and resources on nonfamilial succession planning. “The Changing Hands program is geared toward helping farmers access land, capital, other resources to get started, helping the older generation with succession planning and then to facilitate networking between those two generations because often times those two groups don't end up in the same room together.”

“In Oregon we have a pretty robust land use policy and land preservation is pretty well covered. But what’s not happening is the networking/matchmaking space for people to connect with each other,” said Abigail. “There’s OR Farmlink but there’s not a lot of support that comes along with that.” OR Farmlink (oregonfarmlink.org/) is a website run by Friends of Family Farmers where young farmers looking for land and landowners looking to lease or transition their land can create profiles and get connected.

While their focus on intergenerational transmission includes working with families, Abigail said they are looking for more stories of communal living or non-nuclear arrangements. “I think that’s a big part of the work: developing new and different ways to get creative about living together so everyone can get what they need.” In a recent series on farm succession that Changing Hands published in Capital Press (it can found online at roguefarmcorps.org/changinghands), Abigail said they tried to highlight more nonfamilial arrangements but “they’re harder to find,” which echoes what Beth said: “Our society doesn't really provide any mentorship [around multigenerational communal land tending], examples of what to expect, how it goes. So people are just figuring it out by themselves and there’s a lack of role modeling.”

I also spoke with Nellie McAdams, who runs the Oregon Agricultural Heritage Program, who highlighted land trusts and donating land to local tribes as other innovative examples of non-familial land succession. Land trusts can be a way of keeping communal land, founded with a common set of values, in use for a particular purpose, though there is a question of what third party is making sure those provisions are met. While many individual property owners have donated or willed their land to local tribes, the Coalition of Oregon Land Trusts is starting a Native lands project to explore this in a more organized way. There is also a land trust forming that will specifically hold land in trust for Black and indigenous farmers and farmers of color (BIPOC), with a focus on the Portland metro area.

A final resource is that in 2019, the Oregon Agricultural Heritage Program established a framework to offer a new type of conservation easements for farms and ranches that are taking development and mining rights off the table. While this is only relevant for zoned agricultural land, OAT’s goal is to work with property owners to get grant funding to ‘buy’ development rights, so that farmers can get an influx of funding, for instance to put toward succession planning. As with the SOLC’s conservation easements, this type of easement would also lower the fair market value of the land, making it more affordable for younger farmers. To find out more or stay connected with their work, visit Oregon Agricultural Trust’s website (oregonagtrust.org).

Farm succession is different than communal land project succession, but there’s a lot of overlap. Abigail and RFC are excited to be a resource for folks doing succession planning and people are welcome to reach out to her at abigail@roguefarmcorps.org. I also intend this article to be the first in a series exploring of this topic in collaboration with my partner Sophie Traub. If you have a story about a commune, past or present, and the attempt to transfer leadership, ownership, or connect with the ‘next generation,’ successful or disastrous, I’d love to hear it. Please reach out to me at eliot.feenstra@gmail.com.